The Story

Slowly and surely, the Kubernetes cluster I’ve set up in my company last year moves towards production usage.

The Kubernetes crash course I wrote last year provides a great way to start a fully working cluster, but there’s quite a bit missing when you have service level targets to meet. Kubernetes by itself is quite stable due to its self-healing nature, but there’s much more we can do to make it better.

With a production workload comes a new set of expectations:

- Uptime and stability

- Performance and scalability

- Security

So, I’ve been starting to look into ways that I can make the Kubernetes cluster more stable, and ways to prevent any sort of downtime in the production Deployments.

Uptime and Stability

During deployment, check the status and rollback if necessary

If you have automatic deployments set up (you should), then it’s important to have a mechanism to rollback the Deployment if it fails for whatever reason.

Fortunately, kubectl comes with a command to check the status of your Deployment. If the pods in your Deployment are anything other than “Running”, then the command will fail.

Keep in mind that you will need your liveness and readiness probes set up properly for this. Kubernetes cannot tell if your application is truly working without these probes.

Here’s a script that checks the status of the Deployment for up to 3 minutes, and if it’s still not ready, the command fails. So it’ll run the command to undo the most recent Deployment, effectively rolling back to what it was before deployment.

if ! kubectl rollout status deployment --timeout 3m ${APP_NAME} -n ${NAMESPACE}; then

kubectl rollout undo deployment ${APP_NAME} -n ${NAMESPACE}

exit 1

fi

Node Termination Handler (AWS specific)

The node termination handler is a pod created by AWS to send a signal to your Kubernetes cluster if the node is going to be terminated (either due to spot capacity interruptions, or auto scaling group scale-in events). The node will then be drained, the pods evicted, and a replacement node should spin up to handle these evicted pods if necessary. Set up the EKS Cluster Autoscaler from my previous guide if you haven’t done so.

The setup for this is rather long, and so I will just refer you to the guide written by AWS themselves, here: https://github.com/aws/aws-node-termination-handler

I recommend using the “Queue Processor” mode, as the other mode doesn’t support the Kubernetes Deployment resource.

PriorityClass

A priority class allows you to make certain pods and Deployments more important than others. By default, most of the pods in the kube-system have a higher priority already set. Check out kubectl get priorityclass, you’ll see that your cluster has two priority classes already present.

Now, if your cluster is shared by production and non-production workloads, you will want to set the prodution workloads to have a higher priority (but not higher than system-cluster-critical and system-node-critical). You might wonder why this is important since Kubernetes is self-healing. True, but why play with fire? Outages are often unexpected for a reason, and there’s no harm being cautious.

Here’s one scenario where your production pods might go down. Imagine you’re using spot instances on AWS, and some of your nodes are terminated due to a lack of available spot capacity. Some of your pods will be down because of a lack of node capacity, and they’ll remain down until new nodes come up.

But if you had put your production pods on a higher priority class, Kubernetes would have kicked out the less important pods to make room for your production pods. It’s faster to spin up new pods on existing nodes compared to spinning up new nodes entirely, so if there’s downtime (if there even is one), it’s as short as possible.

Here’s the manifest to create a PriorityClass:

apiVersion: scheduling.k8s.io/v1

kind: PriorityClass

metadata:

name: production

value: 100

# If globalDefault is true, then all future Deployments will use this priority class,

# even if not defined in the Deployment manifest.

globalDefault: false

description: "Used for production pods."

You’ll need to assign your Deployment to the priority class. It’s a one-liner under the template spec section:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: your-deployment-name

spec:

selector:

matchLabels:

app: your-deployment-name

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: your-deployment-name

spec:

containers:

- stuff

priorityClassName: production

PodDisruptionBudget

A pod disruption budget will allow you to set some sort of minimum or maximum disruption that your Deployment can handle.

There are two settings that you can use, and these can be set in either integers or percentages:

- minAvailable

- maxUnavailable

Here’s the manifest to set up a pod disruption budget:

apiVersion: policy/v1beta1

kind: PodDisruptionBudget

metadata:

name: your-pdb

spec:

# Example format for percentages: "75%", "5%", etc.

minAvailable: 1

selector:

matchLabels:

app: your-deployment

This means that there will always be a minimum of 1 pod running at any time.

I believe maxUnavailable is quite self-explanatory. It’s the maximum number of pods that can be unavailable at any time.

Pod Anti-Affinity

This is a way to spread your pods out on all the available nodes, rather than having them all on a single node or two. This way, if a single node goes down for whatever reason, the Deployment will still have some pods running.

This section should be under the template spec of your Deployment manifest, like so:

apiVersion: apps/v1

kind: Deployment

metadata:

name: your-deployment

spec:

selector:

matchLabels:

app: your-deployment

template:

metadata:

labels:

app: your-deployment

spec:

affinity:

podAntiAffinity:

# The other choice is requiredDuringSchedulingIgnoredDuringExecution.

# Using it will prevent your pod from running on a node

# that already has an instance of the pod on it.

preferredDuringSchedulingIgnoredDuringExecution:

- weight: 100

podAffinityTerm:

labelSelector:

# This key-value is the label you've given to your Deployment resource

matchExpressions:

- key: app

operator: In

values:

- your-deployment

# The topology is the set of resources that the anti-affinity acts on.

# In this case, it compares among the hostnames (nodes).

topologyKey: kubernetes.io/hostname

containers:

- name: your-deployment

image: some-url

Integrate monitors and set up alert systems

This doesn’t come with Kubernetes natively, but there are services such as Datadog that offer this. This isn’t actually Kubernetes specific, since you should be doing this no matter what kind of server it is.

The usual monitors should be set up:

- CPU Utilization

- Memory Utilization

- Disk Usage

For Kubernetes specific monitors, there are a few pod statuses that I would like to be notified about:

- CrashloopBackOff

- ImagePullBackOff

- The number of available pods are less than the desired

Performance and Scalability

I’ve already covered a little about auto scaling both your nodes and pods in my previous Kubernetes guide. But here’s a few more things you can do with it.

External Metrics

When it comes to auto scaling, the main two metrics we usually use are CPU utilization and memory utilization. This is easy enough to set up, and is covered in my previous guide.

However, another metric that is often used is queue size, or queue latency. Maybe you have an MQ instance, or Kafka, or even Sidekiq. There are many queue based technologies out there.

There are two things that you’ll need to add: a custom metrics adapter, and an ExternalMetric resource.

Since I’m on the AWS stack, I’ll be using the k8s-cloudwatch-adapter. If your metrics are anywhere other than CloudWatch, you will have to look for an adapter that supports it.

The guide from AWS is here: https://aws.amazon.com/blogs/compute/scaling-kubernetes-deployments-with-amazon-cloudwatch-metrics/, but I’ll add my own guide as well.

To deploy the adapter, run this command. It’s a cluster-wide resource.

kubectl apply -f https://raw.githubusercontent.com/awslabs/k8s-cloudwatch-adapter/master/deploy/adapter.yaml

Your nodes will require the cloudwatch:GetMetricData IAM permission. I won’t cover how to do this.

Next, you’ll need to deploy an ExternalMetric resource. This has to be done in every namespace that requires it.

apiVersion: metrics.aws/v1alpha1

kind: ExternalMetric

metadata:

name: mq-queue-size

spec:

name: mq-queue-size

resource:

resource: "deployment"

queries:

- id: queue_size

metricStat:

metric:

# The easiest way to figure out how to fill in these

# fields is to open the metric itself on CloudWatch.

namespace: "AWS/AmazonMQ"

metricName: "QueueSize"

dimensions:

- name: Broker

value: "broker-name"

- name: Queue

value: "queue-name"

period: 300

stat: Average

unit: Count

returnData: true

Then in your horizontal pod autoscaler, reference the ExternalMetric like this:

kind: HorizontalPodAutoscaler

apiVersion: autoscaling/v2beta1

metadata:

name: your-autoscaler-name

spec:

scaleTargetRef:

apiVersion: apps/v1beta1

kind: Deployment

name: your-deployment-name

minReplicas: 1

maxReplicas: 10

metrics:

- type: External

external:

# This is the name of the ExternalMetric defined above

metricName: mq-queue-size

targetAverageValue: 5

With this, the Deployment should scale up when the average queue size exceeds 5.

Security

Use the simplest base images, and do not run the app as the root user

This isn’t Kubernetes specific, as it concerns your Docker images.

This is much easier to do on compiled languages such as Go, and harder to do on interpreted languages like Ruby on Rails, since they require the whole source code and Rails libraries to be on the image.

Here’s a Go template for building a Docker image. It’s a two stage Dockerfile, where the application is compiled, then in the second stage, the environment is prepared for the application to run in.

# Test and build

FROM golang as builder

ARG USER=unprivileged_user

ARG WORK_DIR=/app

# Allows cross-compilation for the compiled Go app

# This is needed because the two stages use different OSes, since cross-compilation is required.

# You should be able to remove the need for this if you use a golang-alpine variant (I haven't tested this).

ENV CGO_ENABLED 0

# update os and install required packages

RUN apt-get update -qq && apt-get upgrade -y

# Create directories for the user to avoid running as root

RUN groupadd ${USER} && useradd -m -g ${USER} -l ${USER}

RUN mkdir -p ${WORK_DIR} && chown -R ${USER}:${USER} ${WORK_DIR}

# set WORKDIR and USER

WORKDIR ${WORK_DIR}

USER ${USER}

# Copy the local package files to the container's workspace

COPY . ${WORK_DIR}

# verify the modules

RUN go mod verify

# Run tests

RUN go test -cover ./...

# Build app, produces ./app

RUN go build -o app ./main.go

# ----------------

# Produce docker image to run app

FROM alpine

ARG USER=unprivileged_user

ARG WORK_DIR=/app

ARG PORT=8080

ENV PORT=${PORT}

# Create directories for the user to avoid running as root

# https://github.com/mhart/alpine-node/issues/48

RUN addgroup -S ${USER} && adduser -S ${USER} -G ${USER}

# set WORKDIR

WORKDIR ${WORK_DIR}

# Copy the built file from the previous stage to the container's workspace

COPY --chown=0:0 --from=builder ${WORK_DIR}/app ${WORK_DIR}

# Install CA certificates to prevent x509: certificate signed by unknown authority errors

RUN apk update && \

apk add ca-certificates && \

update-ca-certificates && \

rm -rf /var/cache/apk/*

USER ${USER}

EXPOSE ${PORT}

CMD ["./app"]

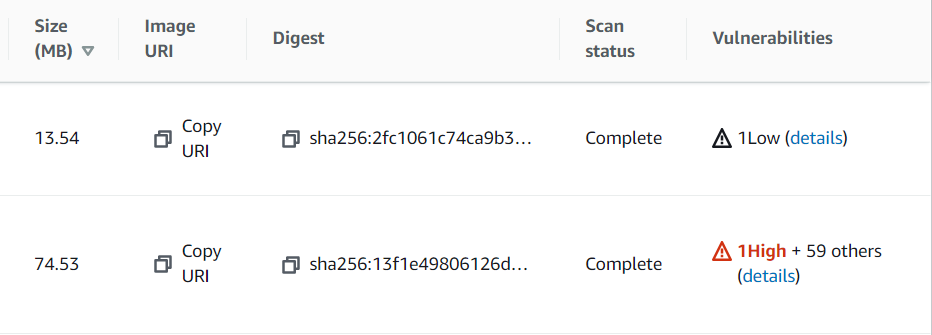

If you want to know why the simplest base image should be used, take a look at the difference between these two images, it’s the same code base, with the debian:buster image originally used:

A smaller image size will also allow your containers to spin up more quickly, because it has to spend less time downloading the image. So, this doesn’t just have a security benefit, it helps performance as well.

Role-Based Access Control (RBAC)

This one is more for your organization’s access control with regards to your employees. Kubernetes, being an orchestration tool, will eventually result in multiple applications deployed onto a single cluster. So, you might want to allow a user to access certain applications, or to allow them to perform certain actions only. This is where roles, role bindings, cluster roles, and cluster role bindings come into play.

There are two concepts to understand here: the role itself, and the role binding. Roles define the resources and actions that are allowed. Role bindings would be where you assign users to take on the defined role. Let’s hop into an example:

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: Role

metadata:

namespace: my-application

name: test-role

rules:

# You can find out the apiGroup of a resource by looking at the `apiVersion` of the manifest.

# For example, a "deployment" would have `apiVersion: apps/v1`, meaning its apiGroup would be "apps".

# You could also run `kubectl api-resources` to check this.

- apiGroups: ["", "apps"]

resources: ["pods", "jobs", "deployments", "configmaps", "secrets", "events"]

verbs: ["get", "list", "watch", "create", "update", "delete", "patch"]

- apiGroups: ["", "batch"]

resources: ["cronjobs"]

verbs: ["*"] # allows all actions on cronjobs

---

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: RoleBinding

metadata:

name: test-rolebinding

namespace: my-application

subjects:

- kind: User

name: john.doe

apiGroup: rbac.authorization.k8s.io

roleRef:

kind: Role

name: test-role

apiGroup: rbac.authorization.k8s.io

If you’re familiar with Kubernetes manifests, I think it should be quite easy to understand. The Role is a list of the actions that are allowed to be taken. There is no denying or excluding actions here, so you have to work around it.

After defining the Role, create a RoleBinding, add your user under subjects, and reference the defined Role under roleRef. The user’s name should be their username on AWS, which should also be present in kubectl edit -n kube-system configmap/aws-auth. They should be added to aws-auth under the mapUsers array, like this:

...

mapUsers: |

- userarn: arn:aws:iam::${aws-account-number}:user/john.doe

username: john.doe

...

ClusterRole and ClusterRoleBinding are pretty much the same thing as Role and RoleBinding, just that they are not confined to a specific namespace. The permissions defined in the ClusterRole would allow the user to perform those actions throughout the whole cluster.

There are some exceptions though - not everything can be put into Role. For example, the ability to act on the Namespace resource will have to be defined using ClusterRole and ClusterRoleBinding. Here’s an example:

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: ClusterRole

metadata:

name: namespace-viewer

rules:

- apiGroups: [""]

resources: ["namespaces"]

verbs: ["get", "list"]

---

apiVersion: rbac.authorization.k8s.io/v1

kind: ClusterRoleBinding

metadata:

name: namespace-viewer-binding

subjects:

- kind: User

name: john.doe

apiGroup: rbac.authorization.k8s.io

- kind: User

name: batman

apiGroup: rbac.authorization.k8s.io

roleRef:

kind: ClusterRole

name: namespace-viewer

apiGroup: rbac.authorization.k8s.io

Comments